Some people are of the view that St. Jerome preferred the Protestant canon of Scripture. This is an interesting view to have considering that the Protestant canon itself didn’t exist at the time of St. Jerome. In fact, the Jewish canon too was not existent during the time St. Jerome1. Why then do people make this claim? Put simply, it is because St. Jerome personally doubted the inspiration of the Greek translations of Scripture, preferring to use only the Hebrew translations. However, St. Jerome, was just a Catholic monk, he had no personal authority to define the canon of Scripture, yet, his translation of the Holy Bible contains2 the 7 Deutrocanonical books, so let’s look at why and how this canon3 was fixed by the Catholic Church and the role of St. Jerome in the official translation of the Catholic Bible4.

Scope of this article:

Who was St. Jerome?

What was his relation to the Roman Church?

What did he think about the Hebrew and Greek translations of Scripture, particularly the Deutrocanonical books5 (which are no longer found in protestant bibles)?

The 1611 KJV contained the Deuterocanonicals

When were the various Biblical canons of scripture fixed?

Who was St. Jerome?

In Brief: St. Jerome (born c. 347, Stridon, Dalmatia—died 419/420, Bethlehem, Palestine; feast day September 30). Best known for translating the Sacred Scriptures from Hebrew into Latin (Vulgate). As protégé of Pope Damasus I, Jerome was given duties in Rome, and he undertook a revision of the Vetus Latina Gospels based on Greek manuscripts. He also updated the Psalter containing the Book of Psalms then in use in Rome, based on the Septuagint. Lived as a hermit, became a priest, served as secretary to Pope Damasus I, established a monastery at Bethlehem in about 389. His biblical, ascetical, monastic, and theological works profoundly influenced the early Middle Ages. Proclaimed - Doctor of the church.6

Was St. Jerome a Roman?

St. Jerome is venerated by both Catholic and Orthodox Christians, however, where would he place himself, within the Catholic Church or within Orthodox Church?

Saint Jerome was born in Strido, Dalmatia (Croatia) in 347. After receiving his education from his father, he was sent to Rome where he studied classical literature and rhetoric. While there, he was baptized by Pope Liberius in 366. By 382 he returned to Rome and Pope Damasus I appointed him as secretary and librarian. He was also commissioned by the pope to render the Bible into Latin. He was spoken of as the next Pope; however, his satirical attacks on the manners of the Roman clergy caused him to make enemies. However, since he enjoyed the patronage of Damasus, no one dared to take any action against him. This clearly shows that St. Jerome was a Roman. He was privileged to be baptized by one pope and to work for another.7 Furthermore, he also submitted to the authority of the Roman Catholic Pontiff and the Roman Catholic Church. This is seen in the following biographical extract on St. Jerome as presented by Britannica Online:

In 375 Jerome began a two-year search for inner peace as a hermit in the desert of Chalcis. The experience was not altogether successful. A novice in spiritual life, he had no expert guide, and, speaking only Latin, he was confronted with Syriac and Greek. Lonely, he begged for letters, and he found desert food a penance, yet he claimed that he was genuinely happy. His response to temptation was incessant prayer and fasting. He learned Hebrew from a Jewish convert, studied Greek, had manuscripts copied for his library and his friends, and carried on a brisk correspondence.

The crisis arrived when Chalcis became involved with ecclesiastical and theological controversies centering on episcopal succession and Trinitarian (on the nature of the relationship of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) and Christological (on the nature of Christ) disputes. Suspected of harboring heretical views (i.e., Sabellianism, which emphasized God’s unity at the expense of the distinct persons), Jerome insisted that the answer to ecclesiastical and theological problems resided in oneness with the Roman bishop. Pope Damasus I did not respond, and Jerome quit the desert for Antioch.

But the most decisive influence on Jerome’s later life was his return to Rome (382–385) as secretary to Pope Damasus I. There he pursued his scholarly work on the Bible and propagated the ascetic life. On Damasus’s urging he wrote some short exegetical tracts and translated two sermons of Origen on the Song of Solomon. More importantly, he revised the Old Latin version of the Gospels on the basis of the best Greek manuscripts at his command and made his first, somewhat unsuccessful, revision of the Old Latin Psalter based on a few Septuagint (Greek translation of the Old Testament) manuscripts.8

St. Jerome in his own words on the Septuagint

Taken from his letter : Apology against the Books of Rufinus by Jerome in 401-402

24. My brother Eusebius writes to me that, when he was at a meeting of African bishops which had been called for certain ecclesiastical affairs, he found there a letter purporting to be written by me, in which I professed penitence and confessed that it was through the influence of the press in my youth that I had been led to turn the Scriptures into Latin from the Hebrew;… It is this same man, then, who wrote this fictitious letter of retractation in my name, making out that my translation of the Hebrew books was bad, who, we now hear, accuses me of having translated the Holy Scriptures with a view to disparage the Septuagint. In any case, whether my translation is right or wrong, I am to be condemned: I must either confess that in my new work I was wrong, or else that by my new version I have aimed a blow at the old…

I do not condemn, I do not censure the Seventy, but I am bold enough to prefer the Apostles to them all. It is the Apostle through whose mouth I hear the voice of Christ, and I read that in the classification of spiritual gifts they are placed before prophets (1 Cor. xii. 28; Eph. iv. 11),

33. In reference to Daniel my answer will be that I did not say that he was not a prophet; on the contrary, I confessed in the very beginning of the Preface that he was a prophet. But I wished to show what was the opinion upheld by the Jews; and what were the arguments on which they relied for its proof. I also told the reader that the version read in the Christian churches was not that of the Septuagint translators but that of Theodotion. It is true, I said that the Septuagint version was in this book very different from the original, and that it was condemned by the right judgment of the churches of Christ; but the fault was not mine who only stated the fact, but that of those who read the version. We have four versions to choose from: those of Aquila, Symmachus, the Seventy, and Theodotion. The churches choose to read Daniel in the version of Theodotion. What sin have I committed in following the judgment of the churches? But when I repeat what the Jews say against the Story of Susanna and the Hymn of the Three Children, and the fables of Bel and the Dragon, which are not contained in the Hebrew Bible, the man who makes this a charge against me proves himself to be a fool and a slanderer; for I explained not what I thought but what they commonly say against us. I did not reply to their opinion in the Preface, because I was studying brevity, and feared that I should seem to he writing not a Preface but a book. I said therefore, "As to which this is not the time to enter into discussion." Otherwise from the fact that I stated that Porphyry had said many things against this prophet, and called, as witnesses of this, Methodius, Eusebius, and Apollinarius, who have replied to his folly in many thousand lines, it will be in his power to accuse me for not baring written in my Preface against the books of Porphyry. If there is any one who pays attention to silly things like this, I must tell him loudly and free that no one is compelled to read what he does not want; that I wrote for those who asked me, not for those who would scorn me, for the grateful not the carping, for the earnest not the indifferent.

34. …Wherever the Seventy agree with the Hebrew, the apostles took their quotations from that translation; but, where they disagree, they set down in Greek what they had found in the Hebrew. And further, I give a challenge to my accuser. I have shown that many things are set down in the New Testament as coming from the older books, which are not to be found in the Septuagint; and I have pointed out that these exist in the Hebrew. Now let him show that there is anything in the New Testament which comes from the Septuagint but which is not found in the Hebrew, and our controversy is at an end.

35. By all this it is made clear, first that the version of the Seventy translators which has gained an established position by having been so long in use, was profitable to the churches, because that by its means the Gentiles heard of the coming of Christ before he came… 9

Jerome Vs Augustine

Jerome preferred to base his translation of the Old Testament on the Hebrew Bible with which most Christians were unfamiliar rather than on the familiar Septuagint—at least through the medium of the Old Latin versions. This preference affected not only his translation of Old Testament books but also his view of the Old Testament canon.

The Septuagint contained several books that are not in the Hebrew Bible. The rabbis of Palestine did not regard as inspired the books in the Septuagint that were not also found in the Hebrew Bible. Eventually, all Jews accepted this view and abandoned books like Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus (Sirach), Tobit, Judith, Baruch, and First and Second Maccabees.

Jerome’s view corresponded to that of the rabbis. He believed that, while these “extra books” may edify Christian readers, the Church should not use them as a source for doctrine. Again, Augustine opposed Jerome. In this instance, Augustine’s view prevailed.10

The KJV and the Deuterocanonicals

For those who accuse the Roman Catholic Church of adding books to the Holy Bible, (in the 1500s), they need to answer why the 1611 KJV Bible contained the Deuterocanonicals. Furthermore, a schedule of Scripture readings for morning and evening prayer included passages from Judith, Wisdom & Ecclesiasticus). It begs the question, why would these passages from these seemingly “uninspired,” “unauthoritative,” “unscriptural” books be included in a protestant prayer book?

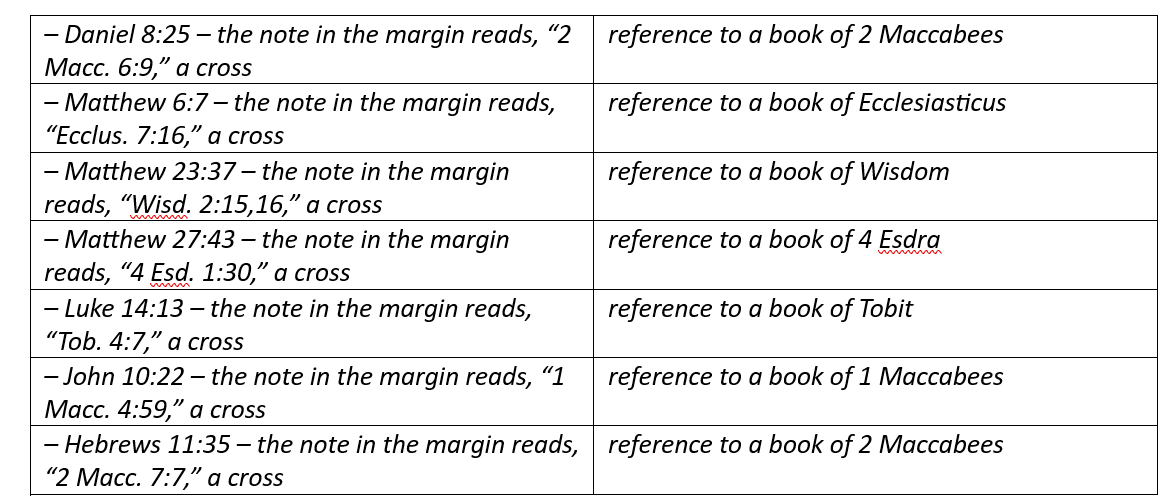

Added to the above is the fact of cross references: The 1611 KJV Bible had the following marginal cross-references to the Deuterocanonical books:

Why are these cross references important?

The simple answer: King James himself thought it important enough to spend time and resources to have these books translated and printed in a protestant bible.

When were the various Biblical canons fixed?

The canon of the Catholic Church was affirmed by

the Council of Rome (AD 382),

the Synod of Hippo (AD 393),

two of the Councils of Carthage (AD 397 and 419),

the Council of Florence (AD 1431–1449) and

finally, as an article of faith, by the Council of Trent11 (AD 1545–1563).

These councils established the Catholic biblical canon12 consisting of 46 books in the Old Testament and 27 books in the New Testament for a total of 73 books. 131415

The canons of the Church of England and English Presbyterians were decided definitively by

the Thirty-Nine Articles (1563) and

the Westminster Confession of Faith (1647), respectively.

The Eastern Orthodox Church additional canons established by

The Synod of Jerusalem (1672)

In Conclusion:

Hopefully, this article objectively proves the historicity of the Catholic Church’s claim that Scripture was canonized by her. It was the work of her children - monks, priests, bishops, and popes working in a unified manner under the Holy Spirit that settled the Canon of Sacred Scripture. This was not the work of one man, nor was it ever private opinion, on the contrary, St. Jerome, who had some reservations about using the Septuagint, laid his own views aside and submitted to the Roman Pontiff, who is the Vicar of Christ on earth.

Ask yourself this question, are you with Christ or against Him? Because there is no middle path. Christ set up His Church, and it is His means of dispensing grace to the whole world.

Further Reading:

1. Did the 1611 King James Bible delete the Deuterocanon?

2. Does Saint Jerome Endorse the Protestant Canon?

3. Saint Jerome: The Perils of a Bible Translator

Footnotes:

The Jews up to the latter half of the first century A.D., past the time of Christ, had no settled canon. St. Jerome on the Deuterocanon, from the blog: Shameless Popery

Nevertheless, Jerome shows deference to the judgment of the Church. In the prologue to Judith, he tells his patron that “because this book is found by the Nicene Council [of A.D. 325] to have been counted among the number of the Sacred Scriptures, I have acquiesced to your request” to translate it. This is interesting because we have only partial records of First Nicaea, and we don’t otherwise know what this ecumenical council said concerning the canon. Jerome and the Deuterocanonicals by Jimmy Akin • 8/29/2023

The most explicit definition of the Catholic Canon is that given by the Council of Trent, Session IV, 1546. For the O. T. its catalogue reads as follows: “The five books of Moses (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy), Josue, Judges, Ruth, the four books of Kings, two of Paralipomenon, the first and second of Esdras (which latter is called Nehemias), Tobias, Judith, Esther, Job, the Davidic Psalter (in number one hundred and fifty Psalms), Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, the Canticle of Canticles, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Isaias, Jeremias, with Baruch, Ezechiel, Daniel, the twelve minor Prophets (Osee, Joel, Amos, Abdias, Jonas, Micheas, Nahum, Habacuc, Sophonias, Aggeus, Zacharias, Malachias), two books of Machabees, the first and second”. The order of books copies that of the Council of Florence, 1442, and in its general plan is that of the Septuagint. The divergence of titles from those found in the Protestant versions is due to the fact that the official Latin Vulgate retained the forms of the Septuagint. (source: Catholic Encyclopedia: Canon of the Holy Scriptures)

The Vulgate was given an official capacity by the Council of Trent (1545–1563) as the touchstone of the biblical canon concerning which parts of books are canonical. The Vulgate was declared to "be held as authentic" by the Catholic Church by the Council of Trent.

(Seven books are accepted as deuterocanonical by all the ancient churches: Tobias, Judith, Baruch, Ecclesiasticus, Wisdom, First and Second Maccabees and also the Greek additions to Esther and Daniel.)

In response to Martin Luther's demands, the Council of Trent on 8 April 1546 approved the present Catholic Bible canon, which includes the deuterocanonical books, and the decision was confirmed by an anathema by vote (24 yea, 15 nay, 16 abstain). The council confirmed the same list as produced at the Council of Florence in 1442, Augustine's 397–419 Councils of Carthage, and probably Damasus' 382 Council of Rome. The Old Testament books that had been rejected by Luther were later termed "deuterocanonical", not indicating a lesser degree of inspiration, but a later time of final approval.

Rüger 1989, p. 302.

"Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent". www.bible-researcher.com. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011.

"Council of Basel 1431–45 A.D. Council Fathers". Papal Encyclicals. 14 December 1431. Archived from the original on 24 April 2013.)

"This is an interesting view to have considering that the Protestant canon itself didn’t exist at the time of St. Jerome." 🤣🤣